Forgotten Indian explorer who uncovered an ancient civilisation

BBC News, Mumbai

Alamy

AlamyAn Indian archaeologist, whose career was marked by brilliance and controversy, made one of the world’s greatest historical discoveries. Yet he remains largely forgotten today.

In the early 1900s, Rakhaldas Banerjee (also spelled Banerji) unearthed Mohenjo-daro – meaning “mound of the dead men” in the Sindhi language – in present-day Pakistan. It was the largest city of the thriving Indus Valley (Harappan) Civilisation, which stretched from north-east Afghanistan to north-west India during the Bronze Age.

Banerjee, an intrepid explorer and talented epigraphist, worked for the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) when the country was under British colonial rule. He spent months travelling to distant corners of the subcontinent, looking for ancient artefacts, ruins and scripts.

But while his discovery of Mohenjo-daro was ground-breaking, Banerjee’s legacy is clouded by disputes. His independent streak and defiance of colonial protocols often landed him in trouble – tainting his reputation and perhaps even erasing parts of his contribution from global memory.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInterestingly, Banerjee’s reports on Mohenjo-daro were never published by the ASI. Archaeologist PK Mishra later accused then ASI chief John Marshall of suppressing Banerjee’s findings and claiming credit for the discovery himself.

“The world knows Marshall discovered the civilisation’s ruins and it is taught in institutions. Banerjee is an insignificant footnote,” Prof Mishra told the Times of India newspaper.

In her book, Finding Forgotten Cities: How the Indus Civilization Was Discovered, historian Nayanjot Lahiri writes that Banerjee “lacked diplomacy and tact and displayed a high-handedness that ruffled feathers”. Her book also sheds light on the controversies he was embroiled in during his time at the ASI.

She notes how once, he attempted to procure inscriptions and images from a museum in north-east India without the approval or knowledge of his boss.

Another time, Banerjee attempted to relocate some stone sculptures from a museum in Bengal to the one he was stationed at without the necessary permissions.

In another instance, he purchased an antique painting for a sum without consulting his superiors who thought he’d paid more than was necessary.

“Banerjee’s many talents seemed to include being always able to rub people the wrong way,” Lahiri writes.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut Banerjee remains a prominent figure among world historians and scholars in Bengal because of his connection with Mohenjo-daro.

He was born in 1885 to a wealthy family in Bengal.

The medieval monuments that dotted Baharampur, the city he grew up in, kindled his interest in history and he pursued the subject in college. But he always had an adventurous streak.

Once, when he was tasked with writing an essay about the Scythian period of Indian history, he travelled to a museum in a neighbouring state to study first-hand sculptures and scripts from that era.

In her book, The Life and Works of Rakhaldas Banerji, author Yama Pande notes how Banerjee joined the ASI as an excavation assistant in 1910 and rose quickly within the ranks to become a superintending archaeologist in western India in 1917.

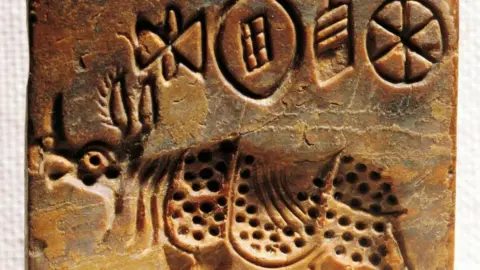

It was in this post that he first set eyes on Mohenjo-daro in Sindh in 1919. In the following years, he conducted a series of excavations at the site that revealed some of the most fascinating finds: ancient Buddhist stupas, coins, seals, pots and microliths.

Between 1922 and 1923, he discovered several layers of ruins that held clues about various urban settlements that had emerged in the region, but most importantly, the oldest one that had existed some 5,300 years ago – the Indus Valley Civilisation.

At that time, historians had not yet discovered the full scale of the Indus Civilisation which, we now know, covered an expanse of approximately 386,000 sq miles (999,735 sq km) along the Indus river valley.

Three seals from Banerjee’s excavation bore images and scripts similar to those from Harappa in the Punjab province in present-day Pakistan. This helped establish a link between the two sites, shedding light on the vast reach of the Indus Valley civilisation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut by 1924, Banerjee’s funds for the project had dried up and he was also transferred to eastern India. He had no further contact with the site, nor did he participate in any excavations there, Pande writes in her book.

But Nayanjot Lahiri notes that Banerjee was transferred at his own request, after becoming entangled in questions over his spending. He had failed to account for several job-related expenses.

It was also revealed that Banerjee had used excavation grants to buy office furniture and his travel expenses were deemed excessive.

His explanations failed to convince his superiors and disciplinary action was recommended. After some negotiation, Banerjee was granted his request and transferred to another region.

Banerjee continued to work with the ASI in eastern India. He spent most of his time in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and oversaw the restoration work of many important monuments.

He resigned from the ASI in 1927, but his departure was marred by controversy. In the years prior to his departure, he became the prime suspect in a case of idol theft.

It all started in October 1925, when Banerjee had visited a revered Hindu shrine in Madhya Pradesh state that housed a stone idol of a Buddhist goddess. Banerjee was accompanied by two low-ranking assistants and two labourers, Lahiri notes in her book.

However, following their visit, the idol went missing, and Banerjee was implicated in its theft. He denied any involvement in the disappearance and an investigation was launched.

The idol was later recovered in Calcutta. Though the case against Banerjee was dismissed and the charges were found to be unsubstantiated, Marshall insisted on his resignation.

After leaving the ASI, Banerjee worked as a professor, but faced financial difficulties because of his lavish lifestyle.

Historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta told the Telegraph newspaper that Banerjee splurged on good food, horse carriages and friends. In 1928, he joined the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) as a professor. He died just two years later at the age of 45.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.